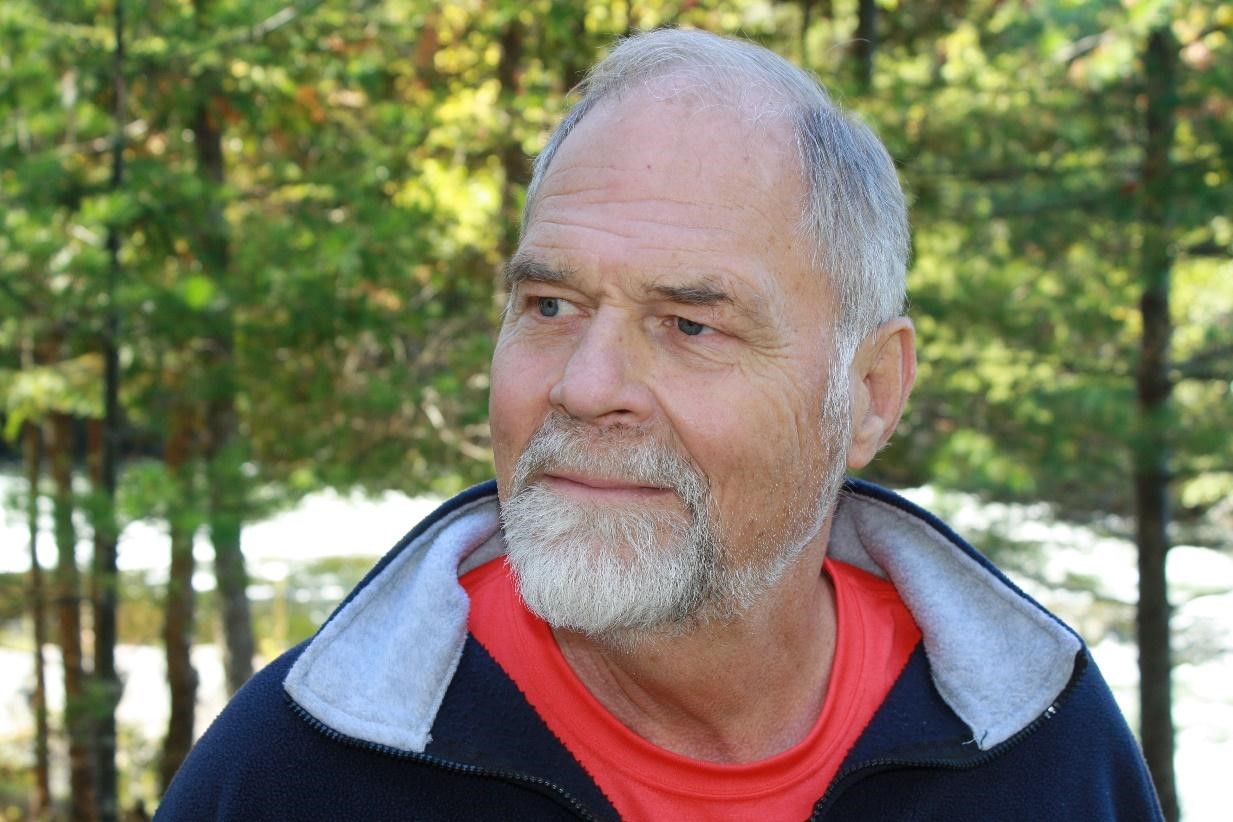

As the summer slips away and PFTF ends this wonderful season, we welcome Sydney Lea. He is a father to five children and grandfather to eight and was Vermont’s poet Laureate from 2011 to 2015. He is the 2021 recipient of the Vermont Governor’s Award for Excellence in the Arts, the State’s highest artistic distinction. He is also a former Pulitzer finalist, winner of the 1998 Poets Prize and founding editor of the New England Review. Sydney is the recipient of fellowships from the Guggenheim, Rockefeller, and Fulbright foundations. For more than four decades he taught at Dartmouth, Yale, Middlebury, Vermont, and Wesleyan, colleges. He also taught at Franklin College in Switzerland and Eotvos Loran University in Budapest. His stories, poems, essays, and criticism have appeared in the New Yorker, the Atlantic, the New Republic, the New York Times Sports Illustrated, and many other periodicals, as well as in more than fifty anthologies. Sydney has a BA and a Ph. D. From Yale University. He has published twenty- three books of poetry in his storied career and just two novels. His second, “Now Look!” was just released. It is a moving story of second chances, missed opportunities and redemption in which he explores the dying of a culture and the destructive grip of addiction. This book and why nature, poetry and contemplation matter more than ever today, are the topics we explore in this episode.

In this Episode you will learn about:

- Now Look! The newest book by Sydney Lea

- The scourge of addiction in small-town America

- The role of nature in shaping a life

- The role of friendship and community in saving a life

- Why a Liberal Arts education matters more than ever

- How to help kids embrace poetry

- Three poets all kids (and parents) should read

Sydney Lee is our guest today. He is a father to five children and grandfather to seven grandchildren. He is the 2021 recipient of the Vermont Governor’s Award for Excellence in the Arts, the State’s highest artistic distinction. He is also a former Pulitzer finalist, and winner of the 1998 Poet’s Prize. He served as founding editor of the New England Review, and was Vermont’s poet Laureate from 2011 to 2015. Sydney is the recipient of fellowships from the Guggenheim, Rockefeller, and Fulbright foundations. For more than four decades he taught at Dartmouth, Yale, Middlebury, Vermont, and Wesleyan, colleges abroad. He taught at Franklin College, in Switzerland, and Eotvos Loran University. In Budapest. His stories, poems, essays, and criticism have appeared in the New Yorker, the Atlantic, the New Republic, the New York Times, Sports Illustrated, and many other periodicals, as well as in more than 50 anthologies. Sydney has a BA and a Ph. D. From Yale University and he has published 23 books of poetry and two novels in his storied career.

His second novel was just released this year, and it is called Now Look! It is a moving story of second chances, missed opportunities and redemption in which he explores the dying of a culture and the destructive grip of addiction. This book is the topic of our conversation today. Welcome Sydney to Parenting for the Future. It is such an honor to have you here!

Sydney Lea: Well, it’s equally an honor to be on with you Mrs. Modeste, I must say.

Petal Modeste: Well, thank you. So, probably because of your lifelong love affair with nature and in particular the nature of New England, you have been described as “a man in the woods, with his head full of books and a man in books with his head full of woods.” But you grew up in Philadelphia. So, when and how did you begin to develop a love for the natural beauty of New England?

Sydney Lea: Well that description. I don’t know who came up with it. Maybe they were trying to say that I was wooden headed. I’m not sure, but at any rate I was raised. Yes, in exurban Philadelphia. But life at home was complex, having a lot to do with addiction, and I had a bachelor uncle who had a farm well outside of that area where I was raised. And I spent every possible moment there. All summer, every school vacation, every weekend. The hired man’s son was my best friend. And we, in our carefree way, fished in the brooks, and we wandered in the woods, and we rode horseback, and we did all kinds of things outdoors, and it stuck. I always think of it as kind of my spiritual home when I write.

Petal Modeste: So when did you yourself move to New England?

Sydney Lea: In 1969. So I’ve been here longer than I’ve been anywhere else by a long shot.

Petal Modeste: That love of New England has been foundational, as you have said, and it shows up in a lot of your work. But you didn’t actually publish your first book until you were 40 years old. So, tell us a little bit about your adult life before then. And how did you determine that poetry would be the correct medium through which to bring your thoughts to the world?

Sydney Lea: Well, if anybody had seen me at 18 years old when I was, I’m afraid to say, a witless, hockey-playing beer-stealing, girl-chasing, male adolescent. They would probably not have said, “Well, that guy, he’s headed to be a poet“ at all. I mean, I wrote the kinds of poems that everybody at that age writes. You know, I broke up with a girlfriend or something like that and all of them, I hope by now have decomposed in a landfill somewhere. But at any rate, I always liked stories. I enjoyed them a lot that factors into this new book a lot especially the stories of really old time New Englanders. I got to college. I’m old enough that ’81 and there were no writing courses at my institution. I did write some fiction but I did it on my own for myself. I would occasionally show it to my two roommates, both of whom were hard scientists, and who were polite, but otherwise pretty uninterested.

And then my senior year long before most Americans could find Vietnam on a map, my roommate, who had taken leave, and went into the army, was one of the first casualties of that conflict. And the more I looked at it the less I thought it was a good idea. I haven’t changed my mind about that, however naive I may have been in my judgments at that time. So what are you going to do when you grow up? I got a job at a private school because I didn’t have credentials to teach in the public school. And even in the comparatively easy environment teaching high school for a year was enough to convince me that no amount of money could make me work that hard ever again in my life. I actually turned in my draft card at a public demonstration and in those days there was an academic deferment. So I said, I’ll go to graduate school. I didn’t have any particularly burning passion to do that. But I liked the fact that when I got to grad school I would be taking only courses that were of particular interest to me. And then I got to the point where I’d done all my classroom training, and there was only left to do the Ph.D. dissertation. And that was a real struggle. I was hired by Dartmouth ABD as they say, all but degree and with the expectation that I would finish that soonish. And the chair of the English department came to me, and he said, You know you really kind of like you around here, but we just can’t keep you unless you finish your dissertation.

I’m really trying. It’s very difficult for me. I was sort of railroaded into a topic by my favorite teacher. A very theoretical topic and theory, and I have never been the best of friends. So I was wrestling with it, and he said, well, I got a solution for you. And I said, Oh, wonderful is he? Going to write it for me? He said, “the kids, you know, they’re clamoring for a creative writing course. We’ll give them one, and you can teach it.” And I fell off my chair. Why on earth would I teach it? He said, “Well, you know it’s not a real course. You just go in and pat them on the back, and express interest and sympathy, and that’ll spare you some preparation, so you’ll have more time to finish your dissertation.”

Petal Modeste: Right.

Sydney Lea: So I started to teach this course, using that verb somewhat loosely. I suddenly fell in love with all my students, and you know the awkwardness and the difficulty they were having expressing, you know, things that were important to them and it kindled a desire in me to write again. And I, as I had done as a short story writer, really as an undergrad on my own. And I take a little detour here – the characters in the new book, the older ones are representative of the group of people I knew. When I was quite a young man who existed in that very remote part of Maine before the advent of electricity, before the advent of power, tools, or kitchen conveniences. They had no means of entertainment from the outside. They had to make their own. And the way they usually did was by way of stories. And I heard these stories in lumber camps and in boats and in kitchens, and everywhere imaginable and I hear the voices of those old men and women in my head every day, even today. I’m always sort of quoting one to myself.

So I wanted somehow to capture the flavor of their talk. I certainly wasn’t Tony Morrison. I wasn’t Willa Cather. I wasn’t Mark Twain. I didn’t have the power, I thought, to do that in dialect, for fear of sounding like I was condescending which was exactly the opposite from the way I felt.

So I came up with this notion, and I don’t know if it’s true or not, I thought, if I try to tell stories in poetry, maybe I can capture some of the rhythms and the cadences of their language without having to imitate them.

My early poems were very much narrative. They were stories, and they were similar to the ones that I had heard and the characters often were borrowed from that particular cast of characters I started to write, and I put poems in places like the New Yorker in the Atlantic. And then the next chairman of the department, didn’t like me, and he said, “You know we have this thing “publish or perish” he said, “you know just as a creative writing course was not a real course”. I said, “Well, I’m just going to let the chips fall where they may”. And I’m going to keep on doing the thing that seems to have engaged my faculties, and I did not get tenure at Dartmouth, but I was almost immediately hired at Middlebury College, which had a tradition of writer professors and that was a better fit, and I was there for a long time as well.

Petal Modeste: So I also mentioned in the introduction that not only did you serve as Poet Laureate of Vermont, you received the Governor’s Award for Excellence in the Arts. What do you value most about the honors you have received, and how have you used them in service of a value that you hold dear?

Sydney Lea: I’m extraordinarily pleased particularly about that Governor’s Award, because that puts me in a company where I don’t belong. I mean, that puts me up with pianist Rudolf Serkin and novelist Bernard Malamud, and novelist Jamaica Kincaid. I’m very honored to have received that award, particularly in a state that, despite this tiny population, it’s brimming with

poets and writers – more per capita than any other State. So I was very pleased by that. But I

enjoyed my tenure as the Poet Laureate. You don’t have any particular obligations. I had just

retired from teaching and our last child had just departed. So I decided I was going to do

something with the distinction and I committed myself to going to any community library that

would invite me, not so much to read my own work, some of it I read, but also I read other

people’s work. But I mostly talked about poetry and what I thought it could accomplish that

other modes of discourse could not. I went to 180 libraries. Some are in really, really tiny

towns. Do you mind if I do these little anecdotes? I’ll tell you one that I particularly like. I was

way up on the Quebec border and there was a man who came in in overalls, and he smelled of

the barn. He was not some stockbroker trying to pass himself off as a farmer.

When I heard him speak, I knew he was real Vermont. Afterwards he came up to me, and he had a book in his hand, he said, well, I really did enjoy that. And I said, What’s the book? He said, it’s Robert Frost’s Mountain interval. That’s one of my favorite collections. He looked at me and said, “How many poems out of it can you say?” I puffed myself up because I bet I could quote four of them. He says I know them all!

So, I quiz him, and I mean I was not quizzing him on “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening”. I liked “Pea Brush”, and “The Gum-Gatherer” and poems I scarcely heard of myself. He recited

every one of them, and it turns out, his father had been a neighbor of Frost. When Frost was making an effort at farming in Vermont. A Failed effort. And they became great friends and every night his dad would read a Robert Frost poem. And I asked him, have you read any other poetry? No, I don’t! It’s like it…

Petal Modeste: No one else exists…

Sydney Lea: So really, it was an amazing incident. But it was great to get out there, you know.

I think that especially at the kind of self-congratulatory ivy institutions at which I taught. There’s a tendency amongst the faculty to think that intelligence stops on the other side of the ivy.

Petal Modeste: Yes.

Sydney Lea: And there were so many interesting bright people, many of them not particularly schooled formally and were just a delight to talk to. So, that was a very gratifying moment in

my life.

Petal Modeste: Yeah, sounds that way. So let’s look at the book. It’s called. Now Look! as I said.

It’s your first novel in 35 years. And I understand you actually started writing it back in 1997.

Sydney Lea: I did.

Petal Modeste: Right so, were you steadily working on it since then, and if not, what made you

come back to it at this point in your life?

Sydney Lea: Well, if there’s a bright side of COVID, that’s what took me back. I had a number of

writing projects. I had done a draft of this way back in 1997, And I knew it wasn’t any good and

I would go back to it periodically, And finally, as I said, when the pandemic arrived, and my wife and I were in semi sequestration., I said, “well, this is the time to finish it off, or else just forget about it.” So, I set my mind to completing that project. And that’s how it happened. I don’t know why I was so resistant to working on it steadily. All’s well that ends well

Petal Modeste: Where does the name come from?

Sydney Lea: “Now Look?”

Petal Modeste: Yeah.

Sydney Lea: Well, it’s something that the wife of one of the main characters says when she recalls her husband who had been a river driver. One of the men that moved logs down river before they started to move logs by motor transportation. Incredibly dangerous. And he was famous for being the best of the best. And in this case there is a younger character and older character. The older character is a great mentor to the younger one. Now the younger one begins his journey as a real knee -walking alcoholic. I mean he functions but he’s really a mess. And this old man is a kind of a mentor, especially about the natural world. And Ironically enough, as the younger man finds his way into recovery. the older man, who suffers a series of just extraordinary tragedies, begins to go the other way. And the hope of the younger man is that he will somehow see the light and get the help he needs to come out of that. In the first full chapter after the prologue we see the older man in his current condition, and his wife is commenting and she remembers that he was always so hardworking and diligent, and cared so much for his kids. And he always had a white shirt and white teeth.

Petal Modeste: White teeth, gorgeous looking man. Yes.

Sydney Lea: And at the very end she says. “Now look!”

Petal Modeste: Now look now, look at him. So, the story really zeroes in on two main themes.

Right? One is the dying North country culture, and the other really focuses on the ravages of

addiction.

And the book is set in a remote town in Northern Maine which obviously evokes all the pleasures and simplicity of life in nature. And want to start with that theme,- the North country

culture before we get to George and Evan, who you were just referring to. What facets of North

country culture do you most want us, your readers, to understand and appreciate as we read

this book?

Sydney Lea: I think a motive, whether acknowledged or not, it’s certainly there in retrospect, is

the old time woodsman, and they were almost exclusively working in the woods in the generation I am remembering, we’ll never see their like again in an age even of electricity, let alone computers. Not to mention artificial intelligence. Oral culture is fading. I was eager not to let it die entirely, to let people know that it did exist at one point. And it’s a very interesting thing about oral culture. How, in a sense. Stories become a kind of community property and often they’re told by different narrators at different times, and different details are emphasized. And not to go too far off base, but I have a Zambian friend, Morgan Chipopo. We met at a literary conference, and he was attempting to put a number of African tales that had only existed in oral culture on the page. And I was simply stunned at the commonality between one oral culture and another. You know the things that they value, the things that they wanted to share, the things that they put out. There is something that we could all as a community make use of in one way or another. And I didn’t want it to be forgotten that there once was, even in this country, a similar culture.

Petal Modeste: And obviously it’s against this backdrop nature stories that we meet George and

Evan, who you’ve started to refer to earlier. They are two men who have been friends for

decades. George has an Ivy League education. He went to Yale as you did. I would describe

him as sentimental, judgmental. He likes a “purple mood” which was my favorite description of

him and he’s loyal to Evan to a fault. Evan, by contrast, is not as educated in the formal sense,

but he’s wise, he’s decent. He’s deeply knowledgeable about nature and life.

And, as you said, the first full chapter after the prologue when we first meet them, Evan is 78,

and he’s struggling with alcoholism. But this is not the person that Evan was for most of his life.

This is not the Evan whose life story George described decades earlier as being intriguing. It’s

not the Evan who has always been, at least to George, generous with his time and his knowledge, his companionship and until later in his life, his heart and soul. So, without giving

too much of the story away, because I do want people to pick up this book, what brought Evan

to the place where we meet him at 78, struggling with alcohol?

Sydney Lea: Evan is no one person from my past. He’s a composite figure. And thank you. I want even more vigorously than you for people to pick up the book, but what I described as a series of almost unbelievable tragedies occurs and he takes to the bottle, which people can do, and then, before they know it unaware, they’ve crossed a certain line. And a lot of people don’t

come back from that. But I took the tragedies of several older men and women I know and kind

put them all together and had him suffer all of them. But his wife who’s an extremely formidable woman and not somebody you’d want to mess with, even physically, she’s aware of what’s become of him, and she’s going through exactly the same tragedies, but somehow or another she is forward enough to keep dealing with life on life’s terms, and he’s increasingly less capable of doing so.

Petal Modeste: George, by contrast, became an alcoholic in his youth and his disease very

nearly destroyed his life. He was drunk at his own wedding. He drove a school bus full of

children while drunk. He was at some point a serial adulterer, and he wrecked his first marriage.

He even once had a fist fight with Evan’s young son, Tommy. But he has also had trauma in his

life right?. His parents were brutally murdered when he was just 9. He had a fourth grade

teacher who bullied him and the woman he probably looked at as a mother (I think she worked

for his uncle) died before he finished college, and that was a very big loss to him. So in

populating his life events, and also even Evan’s, do you mean for us to really empathize with

them, to understand why they turned to alcohol.

Sydney Lea: On the one hand, yes. On the other hand, one of the great obstacles through

recovery is that the addict will say, well, I have reason to be the way I am. One of those old fellows once said, you know, you get drunk. His wife calls up and says the cat died, and he says oh my God! You got to have a drink! And she could call and say the cat lived! Oh, my great! There’s always some reason. And until the time comes, and you say, I just either I’m going to die or I want to do something about this, And I know this autobiographically, you’ll stay in denial as long as you possibly can. Simply because you can’t imagine a life otherwise. Well, life otherwise is infinitely more blessed, to be sure, but that’s very hard to see when you’re in the grip of that disease.

Petal Modeste: So, you have, you just hinted at it, you have your own experience with alcoholism, and you have been blessed several decades ago to go into continuing recovery. How has your own experience with this disease shaped George and Evan?

Sydney Lea: It’s certainly shaped George the younger character. And it showed the degree to

which a kind of thinking is endemic to addicts; a kind of self-centeredness; a capacity to be

judgmental, to fly off the handle and also to not like oneself very much. You know, I’ve heard

addicts described as egomaniacs with inferiority complexes. I know all about that. To the end

of the book, George must resist thinking in those unenlightened ways. And to think in more

enlightened ways is one of the things that he had learned early on in the life of the older man.

Which makes it the sadder for him to be going into the spiral of addiction.

Petal Modeste: So, in many ways Sydney, I feel like both George and Evan are a metaphor, for

all of our lives, right based on where we are born, or our family and the opportunities available

to us, society places certain expectations on us, and sometimes we fulfill them, but often we don’t. And obviously in all our lives some rain falls – illness, death, disappointment, balanced by some triumphs and joys. What role did friendship play in helping each man, George and Evan,

weather the rain in their lives?

Sydney Lea: A lot of those old men, and particularly that one woman on whom Evan’s wife is

based, they were real friends, they were mentors. I remember when I first got into recovery I

went to this guided meditation and the man who was the supervisor said, OK close your eyes now. And he went into this little narrative. You’re walking along a path in the woods, and there’s a brook, and you cross it and on the other side, there’s a little building. within it, there’s someone who’s going to help you maintain your strength and your resistance to your addiction. And that woman was right inside that house. I went inside and she was just a model, almost a force of nature. She really was. Never said a mean word about anybody but tough as nails, you know, had endured all kinds of hardships, you know, particularly financial hardships her first marriage. And I include this in the book. She spent the night virtually every night in the canoe in the middle of the lake because they didn’t have a house. And I remember she lived to be almost 90. And I remember asking her if she was afraid of death she said no, no, not a bit, she said. Life’s been so good to me. How could I complain? And I thought to myself, you’re unhappy because your knee hurts or something. So she’s kind of a model in that sense. Friendship with her and with any number of other men and women up there has been really crucial.

Petal Modeste: and then there’s also Woodstown, which I believe is where Evan and George’s

friendship, kind of formed, and it seems to play sort of an anchoring role both in the book and

obviously in their relationships. perhaps allowing each to find redemption. What did it mean to

you to have that place, Woodstown? Tell me what you wanted most to accomplish with Woodstown.

Sydney Lea: It’s based on a town I know well. 70 year-round Inhabitants where all those old

people live and where I was first taken 1953 by my dad. He died way too young. He had been in

the Forest Service nearby when he was a young man and he wanted to show us what it was

like, and I was just hooked immediately. He had hired an outfitter, legendary man named Carter

White who was of that generation. I just thought he was God. I mean, you want to see a beaver? Okay, we’ll go see one. Wanna see a buck beer? Okay, let’s go around the corner there. I’ll call him Moose, you know. I mean, I just thought he was absolutely magic. And my dad and mom bought a place up there in 1963. Unfortunately, my dad had just one summer there

before he passed away. But in in 1967 my mother’s alcoholism was really in high gear after my

dad died. And the place that she had bought had turned into a kind of a drunken free for all. So

for $500 I bought a little camp down on the river between two lakes which I still own, and

which my wife and I are just back from. And that’s somewhat alluded to in the book. George

gets the camp of his own. So I knew this is less true now, because, having a lot of children, I

don’t get around the town. Small as it is, it’s now grandchildren 7, about to be 8 – I don’t get

around as much, and the old timers have died, and new people have moved in, more leaving

than moving in, Alas.. But at that time I knew absolutely everybody in town. And so that sense

of community that particularly prevailed in the time I’m evoking, very, very important, I think,

not only to me, but also to the book.

Petal Modeste: So, The book touches actually on many things that I think we are grappling with

as individuals and as a global society. Substance abuse, of course. Alcoholism, mental health

challenges, the loss of identity, polarization, fear. And in some ways it also gives us a sense of

how we might navigate those challenges. Community, enjoying and preserving the wonders of

nature, being brave enough to give second chances, and human enough to be empathetic. Why was it important at this phase of your life? We talked earlier about the fact that COVID sort of

got you back to writing this, I feel that this was an important story to tell at this moment. And if

you feel that, why do you think that’s the case?

Sydney Lea: Well, you know, people think of idyllic country life, simple. Boy addiction.

It’s just a scourge in that part of the world. There’s a paper mill fairly close by, which is the

biggest employer by far in a very poor country. And if you’re not working at the mill, you’re on drugs or alcohol. I hate to say that, but it’s pretty much true. If somebody wanted to hire, say, a carpenter. To find one who would be reliable and not addled when he or she showed up is a very, very difficult thing to do, or any other kind of tradesman. Because they’re all at the mill, and why wouldn’t they be? They get benefits. They get good wages for the area, particularly, they get a lot of time off and they get good food at the plant. Particularly with the introduction of the Fentanyl business. People are dying all the time. I think those diseases are out there, and certain people are more susceptible to them than others. I certainly was. I didn’t gradually become drunk. I was drunk from the day I started. I was 11 years old, and my Buddy, the farmer’s son, stole a bottle of wine, and I woke up, and I was covered in my own vomit. I was lying in a field. I was being eaten alive by mosquitoes. And I just couldn’t wait to do it again. Whereas, my friend said, “boy, I don’t like that. I’m never

going to do that again.” That was the difference in our makeup. I don’t know to what degree

you want to be involved in political consideration on the show. But I think as a society, there

are a lot of people who are doing awful, awful well, and the rest of population is going the

another way and that old temptation to take the escape is right there. Now. I don’t say that that

accounts for everything cause there are rich addicts as much as there are poor addicts, but

in particular, those people who don’t see a whole lot of hope for themselves or for those succeeding generations, they want to check out. And I understand that. And I feel that the

remedies are societal. I mean, I think we have to do better. Take care of young people, take

care for old people, make sure everybody gets an education, If he or she needs it or wants it.

Make sure people can get to a doctor. I mean I have neighbors here in a poor part of Vermont

who are choosing between going to the doctor and eating. And it’s unconscionable. Some

people are, you know, making millions of dollars literally a week while others are struggle on

food stamps, which some people want to take away because they think it’s to spoil them. My

God!

Petal Modeste: I absolutely agree with you. It’s astonishing. In a place like this, where we have

There are so many people with nothing. We should be ashamed. This is not something to be proud of and so part of what I would love us to embrace on this podcast is this idea that we want everyone as much as possible to have a better chance, and not just those who are wealthy or educated, etc. And parents have a big role to play in that we can vote, we can sit on our school boards. We can choose to raise our children with an understanding of what it means to be a human being, and how to see humanness in others. so that as they grow and find their own path they never forget.

Sydney Lea: This is unhappiness that is being horrendously exploited – it’s got to be somebody’s

fault. It’s not our system’s fault. I think maybe the most reassuring thing I ever heard as a parent was on my eightieth birthday and my daughter said, let’s go around the table and say what we like most about dad or grandpa. My Oldest boy who’s now 50, said, “what I owe to him most is an understanding that there’s not just one kind of person and that intelligence and gifts can exist at what some would regard as the lowest levels of society.” I didn’t set out to do that. I don’t know what was in my character. 50% of my friends are working class people. That’s the way it is. It’s partly because of where I live, but it’s always been a preference. I mean the farmer’s son with my buddy, not my friends from the Tony, little white private school that I attended.

Petal Modeste: We zeroed in on a number of things today in our conversation, including obviously nature and writing, both of which are very important to you. And we also talked about how the world is evolving the AI, and instant gratification and smartphones, and all of that; that’s in some ways pushing away a simpler, richer existence where nature is the playground. It’s the backdrop, and people can spend time with their own thoughts, (really appreciate their humanness, and try to connect more authentically with each other, whether it’s through writing as you do or in other ways. And I think I am correct in saying that a lot of the parents who listen to this podcast, while we appreciate the promise and the accessibility of technology, we also want to be very intentional about weaving into our children’s lives the simpler pleasures. We talked a little bit about your children and your grandchildren soon to be eight of them. How do you share your love of nature with them?

Sydney Lea: It’s just the way they were raised. I mean where we live, and given a mother and

father who loves the outdoors. And you know what, I proceed through the woods at a rather more stately pace at 81 than I did when I was say 20, but I’m out there every day. I didn’t design it that way. Of course I taught them certain things. You know how to catch a fish. That sort of thing. But you know what you were saying really resonates with me, and it’s one of the most worrisome aspects of technology for me and I can speak of it kind of metaphorically. I mentioned that when I first went to that part of the world as a 9 year old, I was in utter awe. I’d never seen a natural landscape like this, and I’d never seen people so at home in the natural landscape. Last summer I was looking out at the lake, and I saw a young couple, and the man was rowing, and his wife was fishing in the bow, and his two children, just looking at their smartphones.

Petal Modeste: No.

Sydney Lea: I said, boy, put that down and look around. That was astonishing, and also troubling to me. People have Facebook friends and that’s fine. But you have to have friends too – know them, know what they look like, and how they act, and the sound of their voice, how they smell anything you know to reveal their essential humanity which you can’t do by just confronting a set of electrons. Now Of course I’m conscious of the fact that old folks are always thinking the world’s going to hell. I understand that. But I can make some judgments but those are private thoughts now, public thanks to you.

Petal Modeste: Now public on the Podcast, Sydney.

Sydney Lea: Thank you, Petal, for that.

Petal Modeste: Before we wrap up, I want to talk a little bit about poetry. You have said that “Poetry, perhaps more than most written arts, can simultaneously prompt. Inner reflections

and consideration of ultimates; can touch, and the ambiguity of our thoughts, perceptions, and

feelings in ways other genres are not as well equipped to do.” How can parents in their everyday lives encourage their children to engage with poetry, whether it’s reading it, or even experimenting with composition.

Sydney Lea: Well, children are going to be what they’re going to be, They don’t necessarily turn

out to be what you think they should turn out to be. I think I would talk enthusiastically about poetry and what it did for me. Maybe I should have done what Robert Frost’s old Neighbor did.

Petal Modeste: Read to them every night.

Sydney Lea: I have done that occasionally, but it wasn’t every night, and I didn’t ram anything down anybody’s throat, but I think for me, just merely to talk about the pleasures in terms of self-

fulfillment. I could explain that either directly or obliquely over the years to all these kids. One of them, the youngest, is an astonishingly good poet at her age. she’s training to be a clinical mental health counselor. But she’s a really good poet, I must say. Her older sister took a Master’s degree at NYU in food studies, not just how to cook, but you know, issues of social justice and distribution, and she is also an astonishingly good fiction writer. My oldest son went to the famous University of Iowa Writers Workshop and he published the book of shorter stories. But he’s a maker of custom guitars, electric guitars for bands that are famous to people younger than me. His book of stories called Wild Punch evokes the culture of the illustrious in New England better than I’ve ever done.

Petal Modeste: They can always write, they can write for pleasure, they don’t have to be published. They can allow their children to experience poetry and creative arts of all types. Poetry has its own power , and it seems it’s still an important exposure for children to have. And that brings me to my penultimate question for you, which is, when we think of curricula within the US, do you think it is important that there is some sort of poetry present, whether it’s a robust curriculum of itself, or just the exposure to this art form.

Sydney Lea: Yes, I do. You know it’s a larger issue. I mean the whole STEM thing is fine. But

we’re so somehow concentrated on technology and engineering and cyberspace and what have

you. Here in Vermont, several poets laureate some who succeed, and some who precede me

are on a kind of a campaign because the State University system is increasingly cutting not merely courses in poetry, but the humanities in general. Maybe I’m sentimental about the humanities, but I think I think a world that doesn’t have a dimension of art of some kind or humanities, it’s not necessarily impoverished, but it’s not as rich as it could be one of the things we’ve trying to point out is that we studies have been done, and the arts community in Vermont contributes. an astonishing amount of money, $900 million dollars of wealth per year, by way of theater readings, concerts. What have you. So there’s a more vulgar reason to try and stick by them as well,

Petal Modeste: okay. Nearly last question, I said, penultimate before. But I realize I have two

more. One is: if you could recommend 3 poets, not you, and not Robert Frost, 3 poets that you

I think every child should know by the end of their high school years. Who would they be?

Sydney Lea: I’ll choose three, one is an important American poet, Edward Arlington Robinson,

who wrote about small town New England life like me. Whitman is a national institution. You

ought to know something about Walt Whitman. And then there was a long period of time where women, however gifted as poets, were really under noticed And I have so many women poets whom I admire enormously and one of them is the late Maxine Kumin, who was US Poet

Laureate back when they called it Poetry Advisor to the Library of Congress.

Petal Modeste: so as you reflect, Sydney, on your career as a poet, as a writer as a teacher and your work as a conservationist (which we didn’t actually touch on today), and obviously on your roles as a husband, a father, grandfather, friend. What word, what mantra, or even poem has consistently most inspired you; inspired you to rise again when you fell; to persevere in the face of great obstacles; to remain anchored in nature and in story and in love?

Sydney Lea: I’m sorry to keep lionizing Robert Frost, but I’ve directed that on my headstone some lines from his famous poem, called “Birches” be inscribed, and it’s “earth’s the right place for love. I don’t know where it’s likely to go better.” I have to remember the primacy of human affection. If that is set aside in favor of some other pursuit, I don’t think that the result is ever a happy one! And I can be as self-distracted and self-absorbed as the next person. But if I remember that there’s a way out, and that’s the way to it, I’ll be alright.

Petal Modeste: Thank you so much, Sydney, for spending this time with us today. It’s been an absolute pleasure to talk to you, really. Maybe you will come back and just read us poetry one time but it was wonderful to meet you and to and to talk to you today. Thank you.

Sydney Lea: Believe me, on the basis of this conversation, the best of such I may ever have had. I’ll come back and do anything you want, Petal.

Petal Modeste: Thank you so much!

Subscribe to the PFTF podcast

The "Parenting for the Future" podcast connects you the experts leading the charge toward a brighter future. Gain fresh perspectives and actionable advice for nurturing future-ready kids.