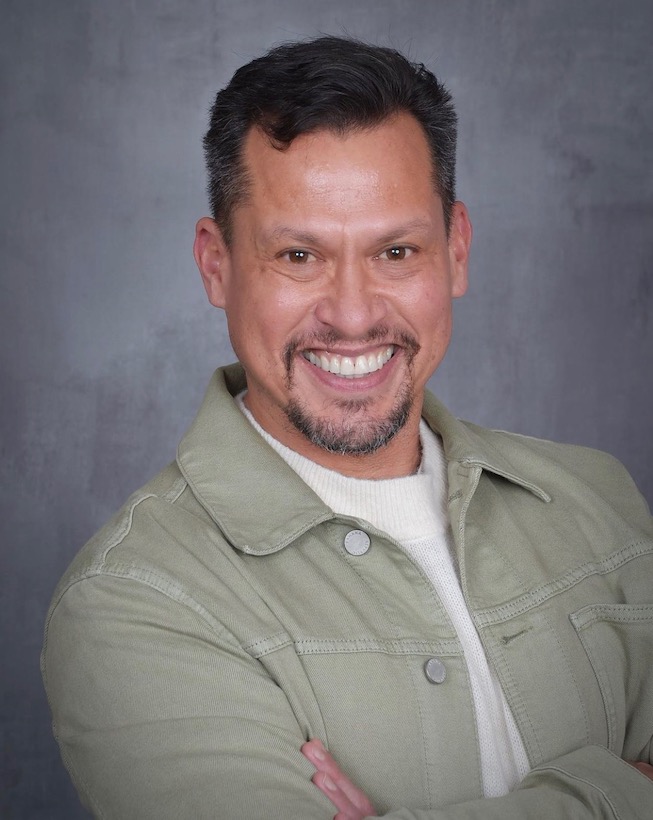

Ed Center is a father to two children, an educator by profess and the founder of

“The Village Well”, a positive parenting platform for parents and caregivers of children of color,

neuro diverse children and other children with unique needs. The Village Well offers coaching

and culturally grounded tools and learning experiences to help parents decolonize their

parenting, tap into the wisdom of their own cultures and interrupt intergenerational pain.

The Village Well also works extensively with educators to give families wraparound support, so they

can ultimately find greater connection, calm and joy. Ed is a recognized parenting expert and

has worked with major corporations, including Salesforce and Lyft, leading educational

institutions, including the University of California, San Francisco, the Monarch School, the Stern

School, leading nonprofits and governmental agencies, including the Y.M.C.A. The San Francisco

Department of Children, Youth and their Families, and various foundations. Ed has a Bachelors

from the University of California, Davis, and is a certified, positive, parenting educator.

In this episode you will learn:

- What it means to “decolonize” your parenting

- How to leverage the wisdom of your cultural background in your parenting

- Why it is important to interrupt intergenerational pain to create healthy, thriving

families - How to apply positive parenting principles to common and not-so-common

parenting challenges

Petal Modeste: Ed Center is a father to two children, an educator by profess and the founder of “The Village Well”, a positive parenting platform for parents and caregivers of children of color, neuro diverse children and other children with unique needs. The village well offers coaching and culturally grounded tools and learning experiences to help parents decolonize their parenting. tap into the wisdom of their own cultures and interrupt intergenerational pain. The village well also works extensively with educators to give families wraparound support, so they can ultimately find greater connection, calm and joy. Ed is a recognized parenting expert and has worked with major corporations, including salesforce and Lyft leading educational institutions, including the University of California, San Francisco, the Monarch School, the stern school leading nonprofits and governmental agencies, including the Y.M.C.A. The San Francisco Department of children, youth and their families, and various foundations. Ed has a Bachelors from the University of California, Davis, and is a certified, positive, parenting educator. Welcome Ed, to Parenting for the Future. We are so pleased to have you join us.

Ed Center: Petal, as you are speaking, I was thinking, who is this guy? He sounds amazing, and also your accent is so delicious. I need you to introduce everywhere I go. So I’m going to bring you on tour. When I go to Salesforce or Lyft, or whoever. So you can do my introductions. Thank you so much for having me.

Petal Modeste: You’re welcome, and, be assured I’ll come with you. So you know, I always like to start these conversations, just understanding a little bit about who you are and where you came from, and what led you to your work? I remember you confessing that as a child you drove your parents and teachers bunkers you had big feelings, lots of energy, and you were very impulsive. How did your teachers and parents respond to you? What did they try to do to maintain their own sanity?

Ed Center: Yeah, well, first of all, I will say that I was very blessed to grow up in a very stable family, with very loving parents, who wanted to have children, and were very dedicated to their children, and I was also surrounded by extended family and a lovely neighborhood where we took care of each other’s kids and fantastic educators. So I was so privileged in that regard we didn’t have a lot of money, but the privilege of community and stability and educators. Was such a blessing. And so within that context, I was wired to come into this world as an emo guy right? Like I came in with feelings that I just found to be so big. So confusing. I think a little bit of that was related to my queerness, which I didn’t understand at the time. But not the whole thing, I think, even if I wasn’t going to be gay, that I still would have all these big feelings, and so it felt like a struggle for me to contain these big emotions, and then move through the world in a way that was considered appropriate or correct or right, according to the grownups in my life. And so something that another kid would consider to be a bummer or an inconvenience was a tragedy to me; a grave injustice, and I had to act out against that. And it might be telling truth to power in my own world view and context, or it could be screaming, or it could be rolling on the floor and refusing to do something. And I know that that led to a lot of concerns with my parents and educators about impulse, control and anger management, and depression and things of that sort. I don’t think I was depressed. I think that I just had big feelings. I didn’t know what to do with them and It was very hard for the adults in my life to understand me. I will also say that I got good grades, and so that got me a really good pass in the situation. So as long as I kept my grades up people were able to willing to deal with a certain amount of uniqueness if you will. And so that helped. But it was very trying for everybody around me, and I think it wasn’t until middle school that I started to understand that there were some boundaries in society, and there were social consequences if I didn’t. And then high school when I actually was able to start to manage some of those emotions in a healthier way.

Petal Modeste: How did the response of your parents, your teachers, your community, their response to you when you were in in that place of, you know, just sort of feeling those big feelings and not hiding them right? How did their reaction impact you? If at all

Ed Center: Yeah, yeah. Oh, a lot. So I will say that the educators in my life were instrumental in this as were sports coaches. And because I because they weren’t my parents, they weren’t as triggered by my behaviors, and because they could see me working hard in other ways, they were willing to do the work to be compassionate, understanding, forgiving, nurturing in these situations, even as they tried to hold boundaries like, if you feel that somebody cheated at a resource game, you can’t take the equipment and throw it all over the place. That’s not appropriate, And so, they were willing to work with me. It was much more challenging for my mother and for my mother. She came from a very strict background. So I grew up in Hawaii and my mother grew up in a pineapple plantation village. So her parents immigrated from the Philippines to work the pineapple plantations and she grew up in a very strict upbringing that I now understand is connected to the lack of safety and violence that was happening in the community at the time. And so for her, my big feelings and big actions. Raised alarms and threats. And so she, while also being very loving and nurturing, wanted to stifle that and so for her upbringing it was, I must stop this. And the way to stop this is to punish, threaten, dominate, control. And so what that did for me was at times when she was successful in doing that, I would become very small and scared and compliant then as I got a little older. I decided I wasn’t going to do that. Then my actions got very big and aggressive. The teenage years were very hard for us. Yeah. And I say, now that my mother was Godzilla, and I was King Kong and then my dad and brothers were the little citizens of.

Petal Modeste: Scurrying away

Ed Center: That got very, very difficult, and I now look back on that situation and see with a lot of empathy and respect for my mom, that the ways that I needed to be parenting at the time she didn’t have the tools to do that. I needed somebody who could walk with me through those big feelings and not be scared of them. and she was not equipped to do that. But you know what I’m equipped to do with that right?

Petal Modeste: And yes, exactly. And, you became an educator. You said that you became an educator to help kids like you, and then you and your husband adopted your 2 children through foster care. And you know we’ll spend a little time on the intergenerational pieces later on. But you know, when did you know that you wanted to be a parent? Because, obviously, like you, just you just said it perfectly, which is my mother didn’t have the tools that she needed at the time. But I now do.

Ed Center: Yes.

Petal Modeste: When did you know you wanted to be a parent, and how did the way you were parented? How did that shape the parent you wanted to become?

Ed Center: Yeah. So my husband, Chris and I had the conversation about kids very early on in our relationship. And so it was in the first year, and it was that value, setting conversation right? Are we aligned in our values and hopes and dreams? Right? And so we both agreed that we wanted children, and we also agreed that adoption was the right path for us, and we didn’t know anything about the difference between private and public and international. At that point we just said, adoption seems like the right path. And for me, because I was an educator, I knew that I could love other people’s children. And so I didn’t feel a sense of a strong sense of biology. In this process. I felt a strong sense of wanting to build a family and having connection, and I think also because of my calling as an educator, and my husband is also a social justice warrior that we felt like. This was part of our contribution to the world to offer. You know our love and time and other resources to children who could really benefit from that. And so we decided that was our path. And then maybe almost 10 years later, after we met, we’re going to celebrate our twentieth

anniversary in June. Thank you. If you have any ideas for a big party on the cheap. Let me know. I think I was like 37 the time. And he said, do you want to have kids? And I said, we’ve had this conversation. And he said, No, but like, should we get moving on it? And this is really important, because I can stay in dreams for a long, long time, and he’s very practical and so, he said, I think now might be the time for various reasons, and I did the math, and realized that you know 37 is young but not young. If you’re thinking about a 20-year trajectory, and also like I was imagining that I want to have a life after. Raising kids, I imagine myself, you know, being old and gay and fabulous, and going to brunch with my pearls and chiffon. and also I didn’t want to retire and pay for college at the same time. And so it was like, Okay, let’s do it. By the way, when the second one came along that it screwed up that plan, he will be college age

Petal Modeste: Join the club Ed. Join the Club.

Ed Center: And so we chose to go the foster care route. And so for people who are not familiar, there is private adoption where the birth mother chooses you while she’s pregnant and then you often support her through her pregnancy, and then often are there at the delivery right? And so if you’ve seen the movie Juno, which is great, it’s that story right? And then there is public adoption, which is kids who are in the foster care system. Who are less likely to be reunified with their parents, and so are up for adoption, and that system is much more volatile. It can be scary because the kids may be reunified with their families right? And you are building a family yourself, but you don’t root against Mom to get her life back together. And but then another big factor. So in private adoption can be very expensive and foster adoption. They pay you as far foster parents got you, and so there isn’t a cost, and there’s some financial support. And us being both. Nonprofit workers to Us as well, as align with our social justice calling and so that’s the direction we went.

Petal Modeste: what kind of parent did you intend to be? What are 3 words that you would use to describe your plan for becoming a dad.

Ed Center: Joyful. Physical and I mean physical play. And intentional.

Petal Modeste: Okay. we’ll come back to that. But that’s helpful. So let’s turn now to the village well itself. My first question is, where did the name come from? Why is it called the village Well? it kind of evokes for me. a little bit about what you were talking about, the privilege you had of growing up in community where, you know, everyone is sort of involved in taking care of the children and the children can benefit from the collective wisdom of that community. But I don’t know. So you tell me, where did the name come from?

Ed Center: So I’m glad you said that because II wanted to hear what it invokes for you. So it is absolutely. That’s the wisdom of the community. It takes a village right. I also wanted something that spoke to folks of color almost as a code right? And so a village well, to me connotes a sense of our ancestor right? And whether that is in Asia, South America, Africa, the Caribbean right, like the same sense of a communal place and then also the well is water, which is life, giving right and nurturing, and then the other thing I like is the village. Well, when we come to get the water it’s also a place where we are going to hang out, where we’re going to gossip.

Petal Modeste: The old water cooler.

Ed Center: Yes, and then imagine the aunties hanging out and gossiping while the kids are running around and playing. And this sense of community. And I think that while therapy is wonderful. And while I also do one on one coaching, I think that many people, especially folks of color, heal best in community and do their best work in community. And so I wanted to create a thing if

you will. A parenting, a family, a healing mechanism that involved community, and so that the name to me captured that.

Petal Modeste: And you wanted to create this because you that either it didn’t exist or any sort of resources for parents of color, for parents of neuro, diverse children, etc., you found them deficient. in other words, what were the unmet needs that you’d identified. That said to you, this is, something I’ve got to do.

Ed Center: So that’s a very personal story. I created the village well at the end of the pandemic. I was feeling isolated and alone and struggling as a nuclear family without support. And so now I can kind of see in retrospect the connection and the desire for community. So my story is that in 2021 we were still in quarantine, we were still, the kids were still not in school. And my older kiddo, who is neuro diverse and has a learning difference dyslexia? Which are things that in person schools should be able to handle. But virtual learning was never going work out from them, and then. And so they really struggled to they’re non binary. So I’m using singular and so they really struggled. and I, as an educator. saw this struggle and said to myself, I’ve got this. I’m an educator, you know. I can handle 25 of other people’s kids, I can certainly handle my own. I could not, and it took me a long time to recognize that that the format of learning was never going to work, and what happened is my child resisted and resisted, and I

interpreted that as stubbornness and laziness and so I took on my mom’s ways of parenting, and I threatened and I punished and I took away privileges, and I got into a power struggle, and their mental health started spiraling, and it took me too long to recognize that. And so I saw it as an increase in stubbornness when it was, is a scream that this is not working for me, that I am scared, that I am disconnected, that I am terrified by the world around me and it wasn’t until things got really hard. And so we’re talking about nightly episodes of 2 h every evening, screaming, breaking things. All of our sharp things were in a safe at this, and it was terrifying, and I knew that this was a mental health crisis. At the same time, I could not stop myself from engaging in power struggles, even though it was making it worse So the good news is, we got amazing support for them. We got counselors through a community organization that would come to our house in person during this time. And I even, you know, at 10’clock at night,

when the crisis was going on and support our family, and we got them the help, and they’re doing so much better now and I have so much more understanding of how I can support them. At the same time, I realized I needed help. that my parenting was not meeting the moment that I didn’t have an ability to be strong and calm and support my child the way they needed, and then I was hurting my child through that. and I went out and got parenting support, and none of that worked for me all of the parenting support. I found they were all white women with psychology degrees, and they had a lot of really good things to say a lot of tools, but I couldn’t access the tools because I was so triggered. And so they would say things like, connect before you correct, and, you know, show empathy and care. And I was like when my kid is cussing me out. I cannot show care right like I would go into my own fight flight tools. I had to do some serious healing, and so what I did is seek other forms of support. I meditation and i started a physical practice. I learned a visualization technique called meshing, where you actually visualize yourself as like a net or a screen. And what I learned to do is that when the trigger happened I could pause for 1 second and then I could pause for 3, and then I could pause for 5, and when I got to 5 that was magic, because then you can pause for 5 s You can turn on that rational brain. And one of the metaphors I use I’m so I’m a lifelong soccer player. Right? And so for most people, if you throw a spherical object at their head, they’re going to duck or thrown their hands up in the specific context of the football pitch if a spherical object flies towards my head, I’m going to throw my head back at it hard, and that is rewiring your brain and that’s what I was learning to do with my child. And that was all the difference.

Petal Modeste: Okay, you were learning to do that because you found that all the good advice you were getting, you couldn’t access some of it. do you think that you couldn’t access it really because of how you were parented and what you had learned parenting was like? Or do you think you couldn’t access it because it didn’t speak to you, based on who you were in totality, your queer brown dad?

Ed Center: That’s very astute Petal. You’re not going to let me get away with the easy answer, are you? So first it’s because of the way I was parented in, because I couldn’t figure out how to be calm in those moments. The other thing is for many people of color, including myself. From a very young age, we are, told, both explicitly and implicitly by white people in authority, that the way we show up in the world is wrong.

Petal Modeste: Yes.

Ed Center: And it starts with preschool teachers correcting behavior. It’s saying that how you act is incorrect in this community, how you tell stories and relate to each other. Let’s say verbally or through song versus written, or loud interrupting conversation versus taking your turn, that this is not valid, and we need to correct it to a white mainstream way of operating right? And so we

internalize through this that we have to shed all of these aspects about ourselves. And either we push it away completely or we learn to code switch right? And so we have different voices for the office than we do with our cousins, and often with our cousins. We feel free and so I know my, my word sounds very different when I’m home in Hawaii and I’ve had one glass of wine, and I’m sure for you in Trinidad it’s the same.

Petal Modeste: Well, that’s all the time for me. Don’t get me pissed.

Ed Center: Well I don’t want to get you pissed but I do want to hear and at some point I reached out to a very well-known positive parenting organization and said. I need a person of color who is going to see what I’m going through. And instead of telling me all the things I’m doing wrong. They’re going to say, Here’s what we’re going to do, honey, And the organization said, I’m sorry we can’t help you. And so that was a big queue to me. so when I developed my own techniques, pulling in ways of being calm and grounded and doing healing work aligned with our different cultures. then I had the idea. You know, this is really working for me. I bet I’m not the only person Petal who has this need.

Ed Center: Yes.

Petal Modeste : And that it can work for.

Ed Center: Yes, and so now my goal is to find all of those people, and say you can do the hard work, and you can find a way to parent out of love versus parenting out of survival. You can do it in a safe way, that where you stay connected to your roots and your culture and the things are important to you.

Petal Modeste: This, all makes complete sense to me, because at the village well, you believe that parenting must be positive, culturally grounded, and also promote intergenerational healing. So I kind of want to take all 3, you know, sort of separately for a minute. We know that positive parenting is this research based philosophy that focuses on getting better behavior from our children through deepening connection, but a question that I often get. And sometimes I ask myself that question, Ed is, in everyday life. What does positive parenting look like? I’m thinking of like everyday situations, you have a toddler they have a tantrum? You have a tween who is addicted to her smartphone or gaming. You have a teen, or an older child who has started to vape Tell us how people who practice positive parenting deal with these situations which could be very fraught, Ed. So the first thing that I do is help parents to renew their connection and their relationships with their kids.

Petal Modeste: So that’s step one.

Ed Center: That’s step number one. And so there’s a foundation of making sure that our kids know that they’re loved unconditionally. And for kids that proof is through time, action and attention. It’s not just through saying it, but even for that dam tween who rolls his eyes at you all the time. Right that we are going to show up with unconditional love, and requests for time and full attention together. Whatever that looks like that can be laughter, washing dishes together. That can be family movie night. But it also should be some form of conversation without screens, maybe over a board game, maybe during a walk, whatever, But we want to turn that connection on. And you know you mentioned smartphones and video games. And like, I have come to the conclusion that those are from the devil right. they are very problematic. But they’re problematic for parents, right? Because they distract us from our kids as well.

Petal Modeste: As well. Yes absolutely.

Ed Center: And So turning that connection on is the first thing, and then very different from the parenting coaches I had. What I do is I start offering tools to parents, so I don’t say what you’re doing is wrong. I don’t say don’t punish. I don’t say, don’t yell. I don’t see any of those things. I say, try this. Try this. So let’s use the example of getting out the door in the morning, which so

my parents struggle with so what I offer to parents there is one practically do as much as you can in the night before. And so I recommend kids have a hook at their size level, and they put all their clothes for the next day on that hook. If there’s any sports or activities, the bag goes on that hook, everything’s ready, except maybe lunch in the fridge right? And so you moved it to the night before. Then, for parents get ready yourself ready just 10 min earlier than you usually do, and nowadays that doesn’t mean wake up 10 min earlier. It means. Close your laptop 10 min earlier and get yourself ready so that in the last 10 min before you get out the door. You are done and you can be present with the kids, because so much of the stress of giving directions is we’re shouting it over our shoulder while we’re doing our own thing. And we’re stressed. So in this case we can now go to our tween and say, Hmm, we’re leaving in 10 min. You’re still in your pajamas and your toothbrush is dry. What’s going on here? How can I support you to get ready? We’re making eye contact, right? We are connected. But we’re not playing. then start to do the nudging, cajoling, support work. what we’re doing is building their skills to follow multiple directions during a time in which they are unmotivated Right? And so we forget that that’s a skill. We forget that. Okay, they don’t have the intrinsic motivation necessarily to get out the door and be on time right? Because the truth is for kids, including teens, there’s very little consequence. And so understanding that I am building the skills that they don’t have, and so I’m going to take them through the multiple steps of direction. I’m going to be present. I’m also going to be firm. And then, if it’s still, if it’s still not working. And you feel like they’re actually resisting you. It’s not a skill thing. Then the final thing is for me to hold a consequence there, and I like to do this in what’s called a when then and so when then to me is when you are fully dressed and walk out the door, I will let you choose the music. We play in the car. or it could be. Listen, we need to get out the door. I need you to move now, can you do that? You start moving? And if not, there will be consequences. If we don’t get out the door on time. I’m going to decide what those consequences are later, not getting into it with you. and then disengage and so positive parenting does not have to be soft. It’s definitely not boundary-less.

Petal Modeste: Yes, because, as you’re speaking, I’m thinking about authoritative parenting, which is, being present building connections, making sure kids know that love is unconditional, but also holding them to certain values and setting boundaries and following through. When you say there will be consequences.

Ed Center: It’s holding that boundary. And then as much as possible, being present with my kid to move them through. That’s age appropriate right? Because, like for my youngest my 6-year old, I may say it’s time to get ready. Do you want to choose your clothes? Do you want me to choose your clothes? And then, even if he says he’s going to choose his clothes. I go into the

bedroom and like, anyway, through the process, whereas for my 12- year-old, once I see them in motion. I know they’ve got it, and so I don’t need to follow through there.

Ed Center: Where healing comes in is that in order to do this, and it is very effective in terms of both getting things done as well as helping our kids develop right, helping their brains develop, helping their skills develop. But we have to get past the trauma and wiring that many of us have from our parents, which is, I said it. It should be done. And that’s hard because that got hardwired into us. And those expectations are there. And recognizing that when our parents did that to us, it got the behavior because we want into fight flight.

Petal Modeste: Yeah, we were secured.

Ed Center: Right? But that’s different from skill building.

Petal Modeste: Absolutely. You just did it. Because.

Ed Center: Yes.

Petal Modeste: So let’s talk a little bit now about the other facet of the village. Well, in terms of its approach. To helping parents. It’s a term that you use on the website. You’d use it to me in our pre conversation – decolonizing parenting. What does it actually mean? Because you, say, of course, that parenting needs to be grounded in our own culture? I can guess what it means. But I want you to explain what that means to the parent who is someone whose background was not in the majority. What is it to decolonize your parenting?

Ed Center: Yeah. So I’m going to speak to this specifically from a Filipino context, which is my background. It’s very relatable to others. But I can speak on that with some authority. is so in the Philippines, which was colonized by Spain for 300 years. Right? You had an oppressor who took away land, who subjugated people who validated people based on class and skin color and

afforded rights and privileges based on that and in subjugating people did so with very violent actions. And so what happened is that Filipinos, go into survival mode. And so we’re living in fight or flight, and prevent the bad from happening, and so often raise our children in very strict ways and some of the teachings of the Catholic Church can contribute to that, and so parents in fight or flight, then raise their children out of survival like you must obey me one, because I’m scared of what will happen to you if you don’t. But 2. That’s what I know. That’s how I am being controlled. And so that’s how I know how to control you. And so whipping, beating, Absolute authority. No talking back. I said this, there’s no negotiation becomes embedded into our culture. and then also for my parents. moved to Hawaii to work the pineapple fields, and what I have now learned is what a violent culture that was. There were strikes a lot, and my grandfather participated in those strikes, and they were beaten, In the Filipino community there were 7 men to one woman. And, by the way, I don’t know if you’ve noticed. But Filipinos tend to have like 5 to 10 godparents. That’s why bring in the community and so the on pay day. My grandfather and grandmother and kids, and other families would go into the sugar cane fields and hide, and the men would stand guard with cane knives because they were worried about the bachelors from the other town coming over to cowboy the women.

Petal Modeste: Oh, my God!

Ed Center: I was an adult when I realized what cowboy meant right? And so what I now re recognizes that violence seeped into how my grandparents, raised My mom’s generation. And also I want to say my grandparents were incredibly like loving, supportive people as well. Right? And so there’s this duality right. So some of these traditions which we feel like are part of our culture, They’re not cultural wisdom, they’re survival. And we can decouple our cultural practices from survival. And so, for example, when our parents said, no talking back, no negotiation. I’m like, I want my kids to grow up with a sense of how to self, advocate, negotiate, and set their own boundaries and so I don’t tell my kids they can’t talk back. I don’t tell my kids that they’re not allowed to negotiate. I do say you have to come in a calm tone., you can sit down, and we can have this conversation, and I also try to show my kids that when they negotiate well, in a calm way, I can be reasonable. But that’s very different from the what I say goes philosophy of my parents and grandparents. And then I also want to say that for many folks of color, we are still in survival. And there are still concerns about basic safety and so that complicates the scenario.

Petal Modeste: It’s very interesting. I mentioned this to you when we were talking initially. My 7 year asked me recently. Why is it that I am so strict compared to her dad, who is white and white parents she literally said, compared to parents who are white and you know I had to stop myself. I believe that I’m authoritative, but I also believe that I’m very supportive. I constantly talk to my children and try to show them how much I love them, and that even if we disagree, or here’s something that they don’t like that, that I’m doing that they can, that we can talk things through. I kind of feel like I’m that parent. But I had to stop myself, and of course I’m really grateful for my parents. They held me to exceptionally high standards. They taught me about the fact that the world is very unfair and hostile even to people who look like me. They don’t even wait to see what you have to contribute. They judge you so because of that. You have to work harder than everybody else and I had to stop and say, but wait a second. is this, because they were fearful that I would go out into the world as a black person unprepared for how hostile it could be if they were not this way with me. And so how would you have answered my daughter I’m really interested in how, in this idea of decolonizing our practices of parenting. How you actually respond to that. And how you actually change.

Ed Center: Yeah. So what I want to raise up is that you had the conversation with your daughter. That’s decolonized parenting that you listened, that you spoke, that you thought about it right? And so within that you’re not saying I’m strict because I’m strict right that there is a space for your daughter to have that conversation with you, and I think there was probably also a space for you to have that conversation with your parents as well when things were calm and even. And so you are modeling connection, taking her seriously critical thinking, your own self-evaluation, your own vulnerability in all of that when you answer the question, and when you grapple with your response and show that you’re figuring things out. All of that is incredible. Modeling and a signal of what I call decolonize parenting. And so to share with your daughter, and I don’t know how far back you went, but you know so as I shared with you like my parents. Were raised in a society that was problematic, based on A, B and C right? Being black in the Caribbean, they came from a very I’m making assumptions. They came from a slave trade that was actually much more violent than it was in the United States right?

Petal Modeste: Absolutely.

Ed Center: That they came from a history of intense subjugation as well as resistance. And so what shows up in their parenting is an incredible desire for their children to survive and to escape persecution and subjugation. And sometimes that comes that that fear comes out in strictness. And I want to be strict cause I’m not going to let you get into trouble. I’m not gonna let you get into harm’s way,

Petal Modeste: By the same token as parents particularly to your point. You know parents of color, and so on. Get better at this. we still have extended family right? We still have grandparents and aunts and uncles who might not even be thinking that they need to evolve in this way with whom your children spend time. So how do we also incentivize them to decolonize their approach to giving care to the children in the family.

Ed Center: Yeah, it’s really hard. I haven’t figured it out with my own family, It really depends on how involved, let’s say, grandparents in this case, right on how involved they are. So for my case my parents live in Arizona. My in-laws live 2 and a half hours away, and so we know we’re not changing them and so they are not going to do the work that I’m doing in this lifetime. And so what I will do is prepare my kids for that.

Ed Center: It’s funny they make fun of Chris’s mom, because she’s an immigrant parent who went through scarcity in World War 2, right? Her love language is food. She serves 5 course snacks.

Petal Modeste: I love it!

Ed Center: So We were like when we go to grandma’s house. We are going to eat at specific times, and you really have to do the work to eat all your food, and if you don’t just know that it’s going to be a battle, and you’re going to get judgement.

Petal Modeste: You’re going to get yelled at Yes, yes, so we won’t need for 2 days.

Ed Center: Yes,because you can make it up at grandma’s.

Ed Center: And then also, you know that my mom if they if the kids fight, she will get triggered and start screaming at them. And so we like, prepare for that. And then hopefully, I’m there, cause. And I tell my mom, you’re going to want to scream. So what’s going to happen is, I’m going to need you to like, go into another room and I’ll deal with the situation right and like we have that expectation, it doesn’t work. So I have to like physically, move my mom to another room. But so the expectations are different. So we understand that. And I think that that a net positive thing for my kids. It’s much more complicated when you have a multi-generational family. And people disapprove of your parenting style. And one of the things that I think is very tricky for families of color is that I do see white families having much more access to Mom. If you’re going to be in my house, you’re going to go by my roles, or you’re not going to be allowed in my house. I think that’s much harder for folks of color. We’re really driven to keep extended family in our lives. And so the negotiation between that becomes much harder.

Petal Modeste: Very fraught. Yeah, II think that’s right, I mean, and it’s also actually a really powerful and positive part of our culture that we take care of the generations. It’s a wonderful part of the culture. But that does make this kind of situation much more difficult.

Ed Center: The other thing that I think it’s really important to remind ourselves in that this work is that we live in a specific American capitalist context. and it’s hard to push against that right. So if we were in our, communal village like even to the contemporary communal village. if I was in Hawaii, I would likely be living in the same block as relatives. And so you have support around that, whereas here we don’t have that support

Petal Modeste: It’s not Scandinavia.

Ed Center: In America. We’re kind of doubly screwed, if you will, because we lose the context of our homeland, which is, can be very fraught also, right? Like we do have community support there. But also we don’t have Western European systems of care and structural support. We’re in the wrong place girlfriend.

Petal Modeste: Now you offer coaching, and but also classes. at the Village Well, could you tell us what some of those classes are, and also how do you ensure that parents, regardless of their socioeconomic background. can engage with the village well and benefit from your expertise?

Ed Center: Yeah, so great question. So I do one on one coaching and most are moms or couples who are middle class, parents of color who are trying to parent in a way that’s different from how they were parented. So that’s in terms of classes. I said. I never start with telling people what not to do. But I’m running a thing called the No yelling challenge. And so I I’m running that and the cost to join that. it’s a month long program where you get a lesson every day. And then there’s a community on Whatsapp and joining. That was $10, And so that’s really important to me to have activities that people can interact with our community that are free. I also every first Friday of the month I have a free first Fridays, and that is for anybody to come to as a name implies, there’s no cost, and we if we hang out at lunch pacific time. I’ll give one parenting tool that takes like 10 min, and then take any questions and conversation that come up. So, there are lots of ways to engage on the cheap and then there are other courses and classes that people can take at more like the $200 price point. I’m offering one for parents of spirited children, which is, it’s like me, with the big feelings and the big actions and positive parenting for spirited children. They eat positive parenting for lunch, and so that we need to show up increased connection and increase support, but also like very firm boundaries.

Petal Modeste: Sounds like we should have a whole episode of that. Yes.

Ed Center: But then the main way that I reach lower income is contracting with schools, government associate government organizations. And so, as you mentioned, I work with the department of children, youth, and families in San Francisco. I work with early childhood fields in California. I am. Knock on wood. Going to be entering into a partnership with child welfare in North Carolina for parents who either are coming back from prison, or who have like done the work to say, get sober and get a job and they’re going to be reconnected with their children, who are in foster care like providing support for them.

Petal Modeste: That I haven’t done yet, and so I’m really, you know, the people who come to me want to come to me? Yes, so these folks they’re in it, and it’ll be a different type of interaction. And I’m so excited to figure that out.

Petal Modeste: Yeah, no, that that sounds great. I, you know, at this podcast parenting for the future. We really believe that parents are the architects of the future, and our goal is to give them the knowledge and the tools they need to raise their children, not just to thrive, but to make their unique mark on the world. And I think, yeah, one of the wonderful things about a program like

this one that you’re likely to get to partner with the with the state agencies in North Carolina about is, so many of our children never get the chance to make their contribution to the world, either because of choices we’ve made because of our structures and our societal ills, And so, you know, imagine the impact that helping a parent who is getting their child back from foster. Imagine the impact you can have on that child’s life. If their parents appreciate and learn how to do this. So it’s really, it’s really wonderful.

So we’re running out of time here. And II have one last question for you. For now, Ed, which is you know, from technological advances to climate change, to the democratization of knowledge, to the shifts in demographics. Our world is vastly different than the world we as parents, grew up in. And so. although the village well focuses on families of color raising, how important is it that parents of any background? Engage with this work that you’re doing, because it seems to me that we all have cultures that

we come from and that we could all benefit from positive, culturally grounded parenting that promotes intergenerational healing. If we want to raise children to thrive and make their contribution. Am I right about that? What do you think?

Ed Center: You’re 100% right about that. in a nutshell the parenting approach that I evangelize, if you will, is really about seeing your child for who they are, and supporting them, to develop on their own journey. As you said, so they can make their mark on the world which is not necessarily the mark that I would choose for them right. And in order to do that, we need to create space for love, for connection for time. We need to slow down and be present and then create space for our kids to you know, have conversations with us, have conversations with peers to make mistakes, and learn from those mistakes, and for us to set very clear boundaries that we hold, and then offer a lot of space within those boundaries for expression, freedom and experimentation. And I think that that is important for every child in the world. My calling is that I think that kids of color as well as kids who have behaviors that are challenging for adults have less access to that space; That we’re more likely to be in a survival mode or to be labeled as problematic. And so how do we support them? To thrive within the actual containers of the world that does have rules and consequences, but also to develop as their full selves. And so my mission is to find those kids who have big feelings and employees. Behaviors, and especially for families of color to be able to support those journeys as well as for parents to

find more connection, joy and meaning.

Petal Modeste: Well, thank you, Ed, this was a wonderful discussion, and I really appreciate your not just spending the time with us, but really educating all of us. And especially as a parent of color. It’s especially meaningful to me the way that you’ve dissected what so many of our experiences look like, and how they can creep in to our parenting and not be helpful. I really

hope you’ll come back and visit with us again and I want you to leave by telling our listeners how they can find you, how they can engage with your work.

Ed Center: I am on Instagram at Village Well parenting and on tick tock at queer brown dad and so we will advertise all of our content there. I also put out what I think is a great newsletter every other week. And we will have announcements about what we’re doing there. But I also put out some thoughts about positive conscious parenting in a multi-cultural context. You can find that at my website, Villagewellparenting.com.

Petal Modeste: And I also Petal, I really want to celebrate your journey on this podcast. To you know, it’s people of color controlling the means of communication right? And getting the word out there about what our hopes and dreams are for ourselves and our kids. And I hope that this podcast thrives and gets an, even bigger audience. And I, want to come back soon.

Petal Modeste: Thank you so much, Ed, take care of yourself, and I appreciate your support very, very much. Take care. Okay.

Subscribe to the PFTF podcast

The "Parenting for the Future" podcast connects you the experts leading the charge toward a brighter future. Gain fresh perspectives and actionable advice for nurturing future-ready kids.